Little Rock, Arkansas 1958-59

The “Lost Year” of 1958-59, is less known than the story of the 1957-58 Little Rock Central High desegregation crisis that preceded it.

The Lost Year is a separate, equally significant civil rights historical episode.

ABOUT THE LOST YEAR

SCHOOL CLOSURE

THE STUDENTS

THE COMMUNITY

A TURNING POINT

LESSONS OF THE LOST YEAR

THE LOST YEAR PROJECT

ELEMENTS OF THE LOST YEAR PROJECT

THE WEBSITE

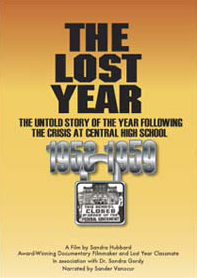

THE DOCUMENTARY

THE BOOK

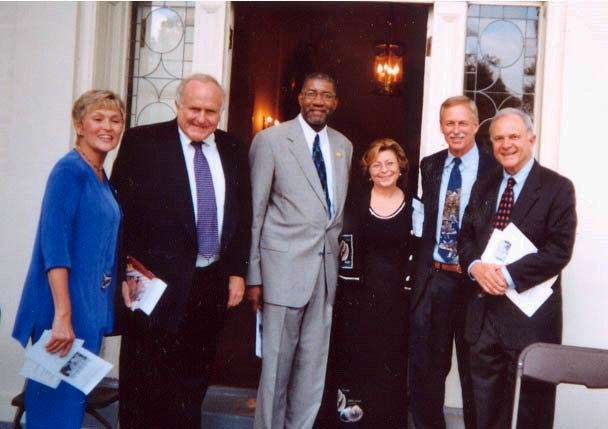

BIOGRAPHIES OF THE LOST YEAR PROJECT

Biography of Sandra Hubbard

Biography of Dr. Sondra Gordy

TALES OF THE LOST YEAR

LOST YEAR TEACHER EXCERPTS

Teachers under contract who went to work everyday but had no high school students to teach

Maud Woods a teacher at Horace Mann. Act 115 targeted NAACP members from working for the state, which included being a public school teacher.

“The joke was on them because they said. ‘Were you a member of the NAACP?” and you said “no”, but they couldn’t keep you from making a contribution. So we doubled it. This is what they asked us to do. Instead of going in stores and charging and buying, you stopped buying and that’s how you made your contribution. Every time you wanted to go buy something, you made a donation.”

Gene Hall head football coach at Central High, recalled that though all other teachers had no interaction with high school students, the football coaches were an exception. Once their peculiar season ended, however, their students scattered to find alternative schooling.

“You know we always take a team picture at the end of the year. We didn’t have, I mean, the day football was over that year, they were gone and we didn’t have them to take that team photo. But we had our school photographer, Bill Lincoln…he had taken individual pictures of all the boys and we made a composite team picture, just their heads, which I still have.”

Leon Adams a black music teacher at Horace Mann, reminds us that Horace Mann High School was a fully accredited black high school, just as its predecessor Dunbar High in Little Rock had been. Adams asked:

“Think about this. The schools in Little Rock, the black schools in Little Rock, were the premier schools in the state. Where else could our students go? We had student who had paid tuition to come in from the county to attend Horace Mann, and now we were asking where can our students go for a quality education?”

Nancy Popperfuss an English teacher at Hall High explained that “there were still some segregationists in the faculties at that time. She said that discussing some subjects among the greater white community was a sensitive task.

“There were some issues that you just didn’t discuss because they were just explosive topics at the time. We have come so far. People just don’t realize how explosive it was.”

Coach Oliver Elders Though he was to coach basketball as a new teacher at Horace Mann High School, Elders never fielded a basketball team that year. He, like other teachers, parents, and students were frustrated.

“The biggest frustration was to not have students. You just can’t conceive of how a teacher feels coming to school every day without students to teach. It’s almost like you’re in gear. You are accustomed to having students around you and presenting and teaching and then you walk into this big gym and nobody’s there. It’s quiet. It’s just like what happens during a holiday and all of a sudden, students are dismissed on a snow day and you’re walkin’ into the gym and there’s just a hush, a quietness. And that went on…every day. It left an impression with you, ‘My goodness, what are we doin’?”

Mary Ann Wright teacher at Hall High said that teachers with differing views avoided discussions with one another.

“I think everybody knew how everybody else felt….I think you tended to gravitate toward the people who felt the way you did. You know, you had to be with these people every day and to be contentious with them would’ve been most unpleasant.”

Jerome Muldrew a teacher at Horace Mann had graduated from Dunbar High in Little Rock. Being a new teacher, he described separate education at Horace Mann (opened in 1956).

“The building was new. It was a beginning. I think that the Little Rock School District was looking at the writing on the wall. That the day was over for second class textbooks and poor facilities and that type of thing.”

Lola Dunnavant a teacher at Central. As schools remained closed the morale among teachers decreased and fears about job insecurity rose. Dunnavant recorded in her diary on February 16, 1959:

“Nearly everybody seems to have lost spirit. They just go from day to day. I do hope that I will not have to leave Little Rock next year, but one never knows. If the schools do not open, I will have to get another job….but to go away alone and leave my home and friends, that’s hard.”

Oliver Elders a black coach at Horace Mann who was new to Little Rock talked about the generally accepted rule that he had heard: blacks should not venture west of High Street.

“There was just a whole lot of agitation then, a whole lot of talking and all that kind of stuff. I did feel that I wasn’t welcome over there and I didn’t intend to go over there to find out whether I was or not. Why would I go over there to find out whether I was or not? I didn’t go over there to shop, I had no friends over there. So I said, ‘fine.”

Jo Ann Royster a “purged” teacher from Central High, was only in her second year of teaching. On May 5, 1958 three segregationist members of the Little Rock School Board declared themselves a quorum and began firing teachers and administrators. They fired 5 blacks and 39 whites. Of these, 27 were from Central and 17 from other schools. Jo Ann Royster said.

“I remember being greatly surprised when I saw my name on that list, but then when I read all the names I felt that was very good company to be in. But it certainly did stir things up, I’ll tell you that. It really got the community behind the schools.”

LOST YEAR STUDENT EXCERPTS

These comments come from the “Lost Year” students affected by the high school closings

One former student who wished to be anonymous said:

“My parents felt that Governor Faubus had no other choice. They were staunch segregationists and totally behind him. They praised him highly. Racial integration was preached to be wrong from the pulpit and confirmed in the home.”

This same student attended high school in a nearby community where she described how she was received in the rural school.

“There were some really sweet students that attended Fuller who accepted us, but others were very angry that we were there…it’s funny that race had nothing to do with this situation. It was, instead, a city versus country issue.”

Roy Wade, a black junior, enrolled in nearby Wrightsville and recalled relationships within the overcrowded school.

“We were able to establish some friendships with some of them, but they felt we were invading their space and their school and (we) hindered them because of the numbers. There were so many until it affected their education as well as our education.”

Paul W. Hoover, Jr. was the son of a prominent Little Rock surgeon. Being white and from a financially secure family he was able to transfer to a private prep school for boys in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He doesn’t remember being “necessarily pleased” with the decision, but Hoover now looks back and says:

“It was the finest and best decision my parents ever made for me because it turned my life around. You had to study, you had to work for everything you got there.”

Grant Cochran, a black sophomore, moved in with his grandparents about sixty miles from Little Rock.

“My grandfather drove a school bus and would pick up all the kids in the rural area and take us down to a highway and then I would catch the yellow bus all the way to Menifee High. Of course, we would have to get up early in the morning, around four or five o’clock, and then we’d get back home about six or seven o’clock in the evening.”

Danny Pytilla was scheduled to be a sophomore at Horace Mann High but he did not attend school anywhere that year. The eldest of eight children, he sadly remembers they lived with their grandmother in a housing project in one of the poorest neighborhoods, Granite Mountain. He explained further:

“We had just lost our mother to a serious illness in May of 1958 and there was no way my grandmother could afford to send me anywhere else to school.”

Dick Gardner was a white junior who lived one block from Central High and waited with friends and neighbors for schools to open in the fall of 1958. By October, Gardner asked his parents to give permission for him to join the U.S. Navy. He joined the Navy at seventeen and served until he was twenty-one.

“We didn’t have a school and we didn’t have a job and it didn’t look too good. The Navy would give me a job. They would train me. I think things would have been different if I had not left home. I know I would have finished high school at Central. I’d have gone to college. My daddy would have seen to that. He would have seen to it.”

Carol Hallum, a white displaced junior, attended T. J. Raney High, a private high school that opened in October of the Lost Year. Many considered it to be a segregationist school since Governor Faubus supported it publicly and solicited donations in public speeches. But Hallum believes some attended because it was free.

“When they said there was going to be a private school and it would not cost anything, my parents said, ‘you’re going.’ I didn’t go to the other private school because it cost. There was tuition for the Baptist High School and we didn’t have the funds for that. So until Raney opened up, I would not have gone to school. There was no other place to send me.”

Toshio Oishi was a Japanese American whose family had been interned during WWII and later worked as laborers on a truck farm in Scott, AR. Because of declining enrollment, all Scott high school students were bussed to nearby schools in England or to Central High School in Little Rock during the crisis year of 1957 – 1958. Oishi’s comments help explain the racial tone of the time.

“I was very concerned during registration and prior to attending Central High of being given a difficult time because my skin was dark from working outdoors on the farm. This turned out to be an unwarranted fear.”

David Scruggs, a white senior from Central High and Sports Editor for the student newspaper, the Tiger, hoped for a career in journalism. He attended the second semester of his senior year at T. J. Raney, a private white school.

“I always felt that year I was at loose ends. I wasn’t studying journalism anymore. I didn’t have a lot of will. My grades were bad. I did not do well. I can’t say I really profited at all academically.”

Jerry Baldwin, a sophomore at Central High, rode the bus to Hazen, AR.

“We rode the Trailway bus from the terminal downtown. My mother had seen an article in the newspaper and called and got me on the list and I was accepted. I attended the whole year, as did all of us that rode the bus.”

Bowman Burns, a black junior from Horace Mann didn’t go to school

“I didn’t go to school that year. I got a job and I thought I would take advantage of it, what it really boiled down to. It really began to soak in that you are going to have to get out there on your own. I wish I had gone on to school now that I look back at it. Because I would have graduated with my own class, when I ended up graduating with the next class.”

Almeta Lanum Smith was to be a junior at Horace Mann High. Instead both she and her sister went to Pine Bluff (about 50 miles away) to attend a black Catholic high school.

“We didn’t have a car. We were just fortunate, we really were. We (my sister and I) went to St. Peter’s in Pine Bluff. And the way we found out, a friend’s father was working down there and he was going every day and coming back and Carmellita Smith was going with her dad and she and my sister were very good buddies. And so my mother asked if we could ride along with them. So that’s what we did”

Myles Adams was a white junior at Hall High but rode a church bus to Conway every day to attend an “academy” that Central Baptist College formed for displaced students.

“When it (the Academy) came up, it was so late in the year. I don’t think that we started until October sometime. It was so late that we wound up going six days a week through June of that year. Then we had some bad winter days and we had to make up for those days. In order for our Academy to have all our credits, we had to meet all those guidelines.”

Edie (Edith Faye Garland) Barentine, a white senior from Hall High, was sent to Oklahoma to live with relatives for her senior year. Before, she was active in her church, served as a white counselor at an all black Methodist camp and participated in mixed-race discussion groups at the YWCA and in private homes. She remembered saying:

“If I ever come face to face with Orval Faubus he will hear what I think of him.’ I wanted someone to blame for what happened in the Lost Year and what happened at Central High. Many, many years later I ended up alone on an elevator with him. He was much older. I noticed his suit was ill-fitting and his shoes were dirty. We made no eye contact, and in that short ride, I thought, ‘this is a man and he is vulnerable, and he is old and tired.’ And all of that hate just left me. His shoes were dirty and I had never stood in his shoes. As he exited the elevator, I looked at him and was able to say ‘It’s good to see you, Governor.”

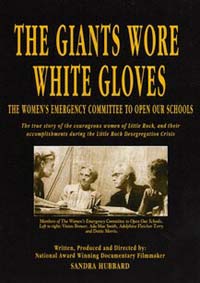

THE GIANTS WORE WHITE GLOVES

TELL US YOUR STORY

One of the main reasons for developing this website is to allow the parties involved to tell their stories. Whether you are a Lost Year classmate, a Lost Year teacher, the parent of a Lost Year classmate, siblings or others involved in this historical time in our city . . . please tell us your stories.

By submitting your story to us, you give your permission for us to use your information. It may be used in the form of an excerpt for this website, a portion of the documentary, or Dr. Gordy’s book.

Your stories will help enrich the experiences of the Lost Year. Please take a few minutes to reflect on your experiences of the Lost Year.

Some questions to prompt your memory

- Please use these as guides to trigger thoughts as you tell your story. None of the questions are required and some won’t apply to your experience.

What school did you attend in 1957 – 1958? What school were you to attend during the 1958 – ’59 school year? What school did you attend during the Lost Year? What was your classification during the Lost Year? (senior, junior, sophomore). - Were you or your family aware that the high schools might be closed? If so, how did they discover this? Was it talked about in your home? Was it talked about among your friends?

- At the beginning of the Lost Year, were you getting ready to begin the year at your normal high school? How did you feel when you got the word that your high school would be closed?

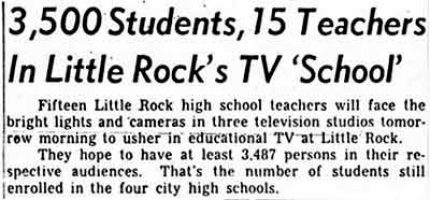

- Do you remember students being taught classes early on television

- What did you think about the school year before, and the desegregation crisis of that year? Were you involved in anyway?

- Do you remember the mood of your family? The mood of your friends?

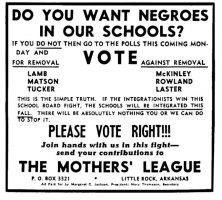

- Were you aware that the school district voters (your parents) were asked to vote either for or against integration, in September of 1959 and that there was no mention on the ballot of keeping the schools opened and integrated? Do you know how your parents voted?

- Were you aware of all four high schools that were closed that year, or only your own? Of your friends, were any of your closest friendships affected?

- Did you go out of state to school? If so, what state did you travel to, and who were you living with? How far did you travel? How did your being gone affect your family?

- Did you stay in Arkansas? Where did you go? How far did you travel, and how?

- Did you receive your education through correspondence courses?

- Did you drop out of school that year?

- What was your memory of the athletics programs at all of the closed high schools?

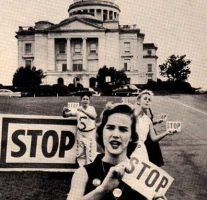

- Do you remember any of the groups that were organized to fight for and against what was happening here in Little Rock? Examples: Against – White Citizens Council, Mother’s League of Central High or the CROSS Campaign

- For opening the public schools: The Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools, the STOP Campaign.

May 5 – Teacher Purge – School Board purged 44 teachers and principals.

- Were you aware of the teacher purge, and the STOP Campaign?

- What was going on in the nation regarding integration / desegregation? What was happening in other communities across the country?

- What did you do about the upcoming school year? (1959-60) Did you think there was a question as to whether they would open, and stay open? Did your parents have any question? Was Faubus active in trying to thwart the opening of the public schools again?

Schools opened August 12th in 1959 – 60 school year.

- Do you consider the experience of the Lost Year a good or bad experience?

- Did you return to your original destination school? Did you graduate?

- Tell me the most uplifting story you can remember about that year.

- Tell me a moment that stood out in your mind, either the day you left home, the day you attended the new school. Were you welcomed or challenged?

- What do you think was learned from the schools being closed that school year?

- What lessons should be learned from the events of the “Lost Year”

- What effect did the experience have on your attitude about integration/desegregation or race?

- What would you say sums up your experience?

[ninja_form id=1]

Please submit your stories using the convenient online form,

or via email to:

Dr. Sondra Gordy, sondrag@uca.edu,

or

Sandra Hubbard, sandyhub111@gmail.com

You may also mail your stories via post to the addresses

on the Contact page

CONTACT US

Dr. Sondra Gordy

History Dept.

P. O. Box 4935

University of Central Arkansas

Conway, AR 72035

Email: sondrag@uca.edu

Phone: 501-450-5629

Sandra Hubbard

Morning Star Studio

1923 Woodland Avenue

Fayetteville, AR 72703

Email: sandyhub111@gmail.com

Phone: 501-519-1677

Additional Research Information for the “Lost Year”

“The Giants Wore White Gloves” – a documentary by Sandra Hubbard – available at the Central High Museum and the Clinton Museum Story.

“Breaking the Silence” – a book written by Dr. Sara Murphy and son Patrick Murhpy. Available at the Central High Museum and at the link provided.

“The Embattled Ladies of Little Rock” – a book written by one of the Women’s Emergency Committee Founders, Vivion Brewer – available at the Central High Museum.

“Empty Classrooms, Empty Hearts” – Arkansas Historical Quarterly Volume LVI Winter 1997 427-442. Dr. Sondra Gordy

“Through a Heroine’s Eyes: Elizabeth Huckaby and the Lost Year” – Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol LXVII NO.2 Summer 2008. Dr. Sondra Gordy